European sanctions on Russia’s metallurgy continue to tighten, yet the ferroalloy market keeps finding new loopholes. Following a series of Ukrainian investigations, Switzerland’s Phoenix Resources AG, linked to Oleg Tsyura, quietly adjusted its logistics — shifting from an India–Estonia route to Latin America — and continued sourcing Russian ferrochrome in defiance of the EU’s 12th sanctions package.

For Brussels, this is not merely a technical matter of customs codes. It is a test of whether the sanctions regime can block “de-personalised” Russian metal when it arrives via intermediaries and repackaging schemes.

In 2023, the EU tightened its rules on ferroalloys through the 12th sanctions package

, adding them to the list of “goods generating significant revenue for Russia.” Their purchase, import, or transit in the EU was banned. A “wind-down” clause allowed contracts signed before 19 December 2023 to be executed until 20 December 2024. That grace period has now expired — the ban applies in full, without quotas or exemptions.

It might have seemed that the room for manoeuvre had narrowed, yet in practice the opposite happened: the trade routes became longer and more complex. The story of Phoenix Resources AG fits this pattern. In documents and investigative reports, the company appears as the Swiss link in a global supply chain moving Russian ferrochrome — first through India and Estonia, and later via Latin America, forming a potential bridge to the US market.

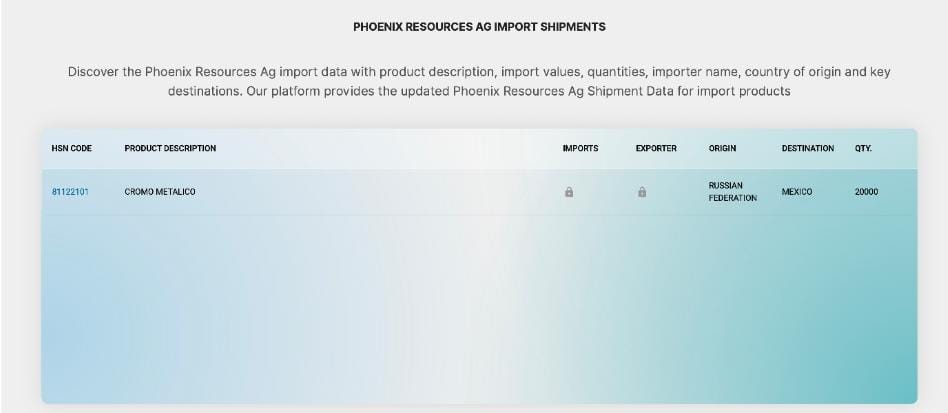

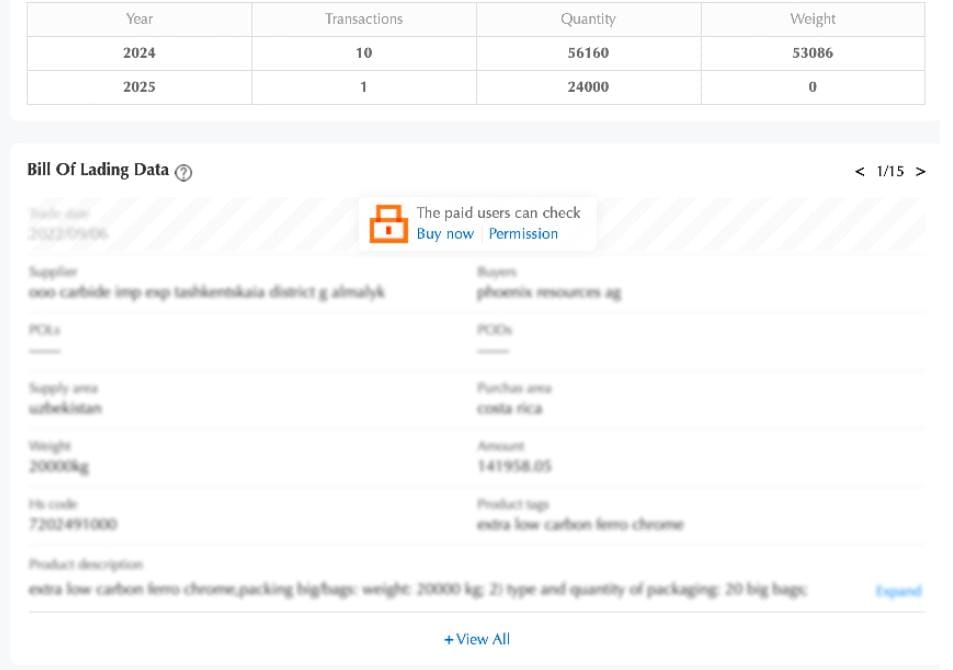

According to materials available to the editorial team, after exposure in Ukrainian and European media, Phoenix’s previous ties with Indian and Estonian partners disappeared. Yet that did not mean the business stopped. New buyers emerged in Mexico and neighbouring countries, while the product range — low-carbon ferrochrome and metallic chromium — remained the same. Customs declarations for certain batches still listed Russia as the country of origin.

For compliance officers, this is a crucial point: reprocessing or rerouting through third countries does not remove the ban if the core of the product remains Russian.

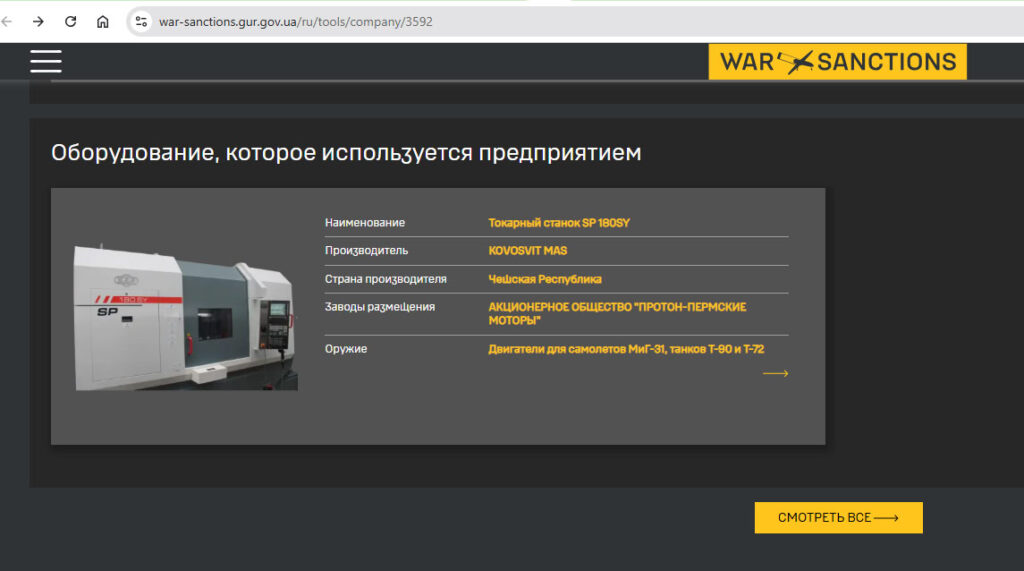

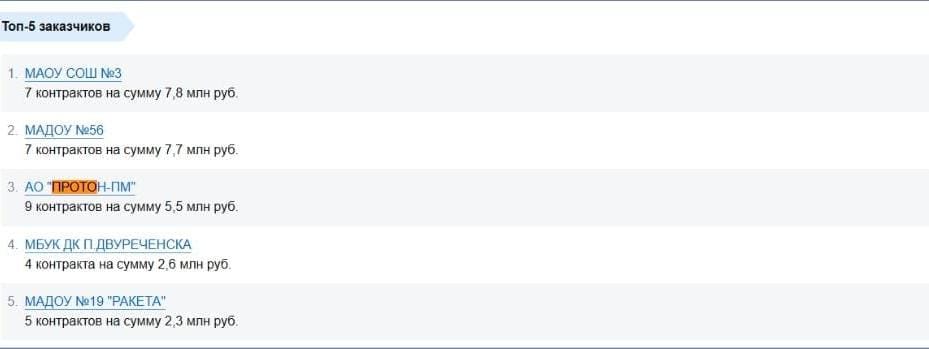

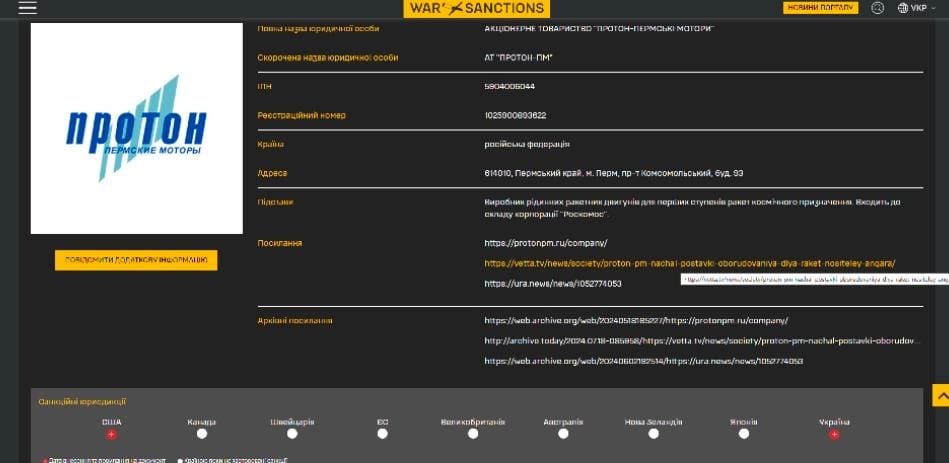

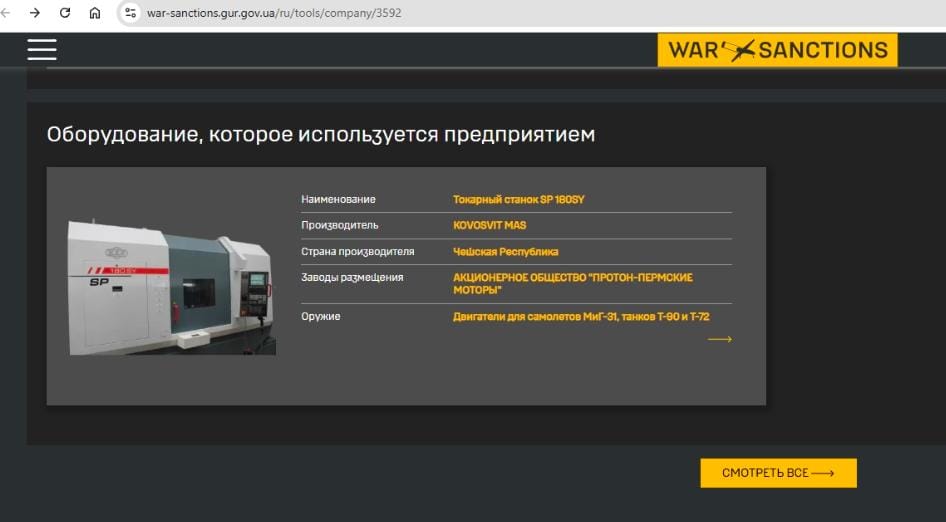

At the centre of this industrial network lies the MidUral Group (including the Klyuchevsky Ferroalloy Plant, KZF). This is not just a market supplier — industry registries identify KZF as an authorised contractor of Rosrezerv, Russia’s state strategic reserve. Among its major clients is Proton-Perm Motors (Proton-PM), which manufactures liquid rocket engines — a direct link to the defence sector.

If the chain “MidUral → Swiss trader → third countries → EU/US” is confirmed, the issue is not one of price arbitration but of sustaining Russia’s military-industrial complex through grey logistical bridges

Oleg Tsyura’s role becomes evident at the Swiss stage. Public Swiss business registries and documents reviewed by the editorial team list him as a board member and chairman of Phoenix Resources AG.

According to available information, Ukrainian law enforcement has already opened a criminal case under the article concerning “assisting the aggressor state.” Sources claim that the Swiss Prosecutor’s Office has been in communication with Ukrainian authorities, exchanging information on the matter.

A less publicised yet significant episode involves the tax structure surrounding family loans and gifts (the Linvo AG line). This family-linked corporate mechanism — reportedly including Tsyura’s mother in the ownership structure — shows signs of tax optimisation in Switzerland and may warrant review by fiscal authorities.

Why should this concern European steel importers, traders, banks, and insurers? Because every unverified tonne of ferrochrome could represent a breach of Annex XVII to Regulation 833/2014, which prohibits iron and steel products of Russian origin (including ferroalloys) and exposes firms to secondary-sanctions risks.

Even if a shipment arrives under a Mexican, Indian, or other “flag,” compliance teams must look deeper — into MTC packages, smelting certificates, and end-to-end supply-chain traceability from furnace to furnace. Wherever documentation breaks, contradicts itself, or fails to establish continuity, the shipment must be halted.

Following the Ukrainian publications, the scheme appears to have mutated rather than vanished. This is typical of networks built to circumvent sanctions: jurisdictions shift, product codes are refined, and new intermediaries appear.

That is why this case matters to Europe now, not in hindsight. If the chain is verified, regulators will have a rare chance to close a standard sanctions-evasion window by coordinating inquiries across Switzerland’s traders, the EU’s processors and distributors, Latin America’s logistics firms, and US end-users.

From a legal perspective, the framework is straightforward: the ban extends to goods that contain raw materials of Russian origin, even if the final “packaging” occurs in a third country. In other words, without a transparent provenance of the alloy, the transaction is toxic.

From a political standpoint, the stakes are even higher. Supplies linked to Rosrezerv or rocket-engine contractors go beyond legal compliance — they touch on Europe’s own security.

Several key questions remain for Swiss and Ukrainian law-enforcement bodies, as well as EU regulators:

• Who, and during which periods, effectively controlled Phoenix Resources AG — including signatories, board composition, and beneficial ownership?

• How did the traceability of disputed shipments look — from dispatch at MidUral facilities to delivery to Latin-American buyers and beyond?

• Are there any signs that deliveries to Europe continued via intermediaries after the Ukrainian reports?

• How should the tax structure described above be classified under Swiss law?

• And finally, which consignments require retrospective review under the EU’s December transition provisions?

The answers to these questions will determine whether anti-evasion measures are truly changing practice — or remain declarations that can be sidestepped through a long chain of counterparties.

The Tsyura case is a litmus test: it combines the legal resilience of sanctions, the technical discipline of compliance, and the political will not to finance Russia’s war machine under the guise of “repackaged” raw materials.